MF: Do you also work on the positioning of the instruments depending on the hall?

JB: Absolutely – for me it’s an incredibly important aspect, not just for the quality of sound and comfort of playing but also as a means of expression. Orchestras have, throughout the ages, been set up in many different ways, depending on the repertoire, the time period, the concert hall and for me it is definitely part of the expressive role of a conductor to be flexible with orchestral seating.

Just to begin with, there are many pieces (particularly written in the last 60 years or so) where the composer asks for specific or unusual seating plans of orchestras because the roles played by certain instruments or groups of instruments do not function in the traditional manner.

The most famous extreme example of this would be Stockhausen’ Gruppen where he asks for three separate orchestras to surround the audience creating the most astonishing surround sound effects.

But there are many examples of pieces placed on stage with different layouts. From Stockhausen’s Fünf weitere Sternzeichen where the strings are placed behind the winds, brasses, harps and percussion and space is left between the conductor and the audience for a solo tuba to move around. Or Boulez’s Rituel where 8 groups of players are asked to be as far away from each other as possible on stage (perhaps an early form of social distancing!).

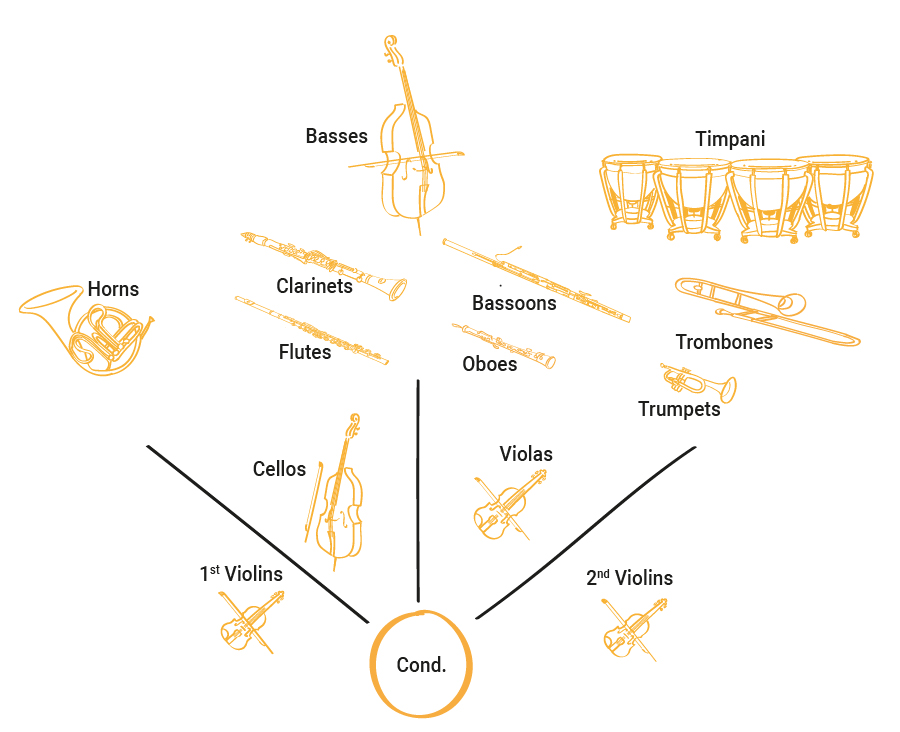

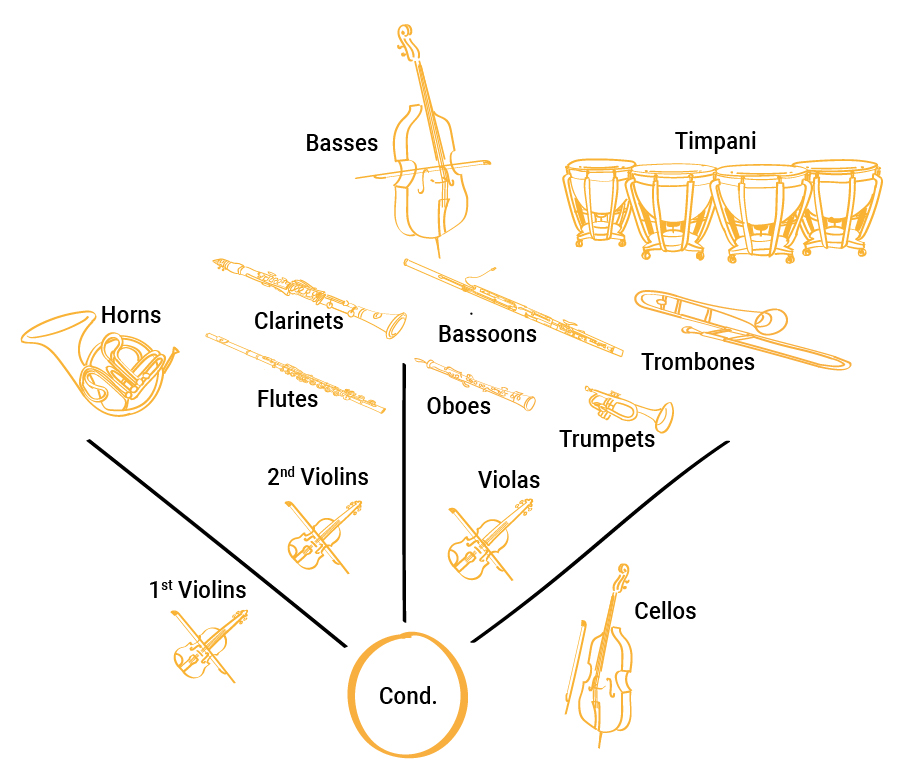

For more traditional repertoire there are some decisions you have to make, for instance where to place your violins. In most music before around 1825(ish), Beethoven, Mozart and Haydn for example, you probably want the 1st violins on the conductor’s left hand side and the 2nd violins on the right hand side, so that the audience will experience a stereo, antiphonal effect as the composers often write dialogues between the violins into their music.

Whereas for some composers like maybe Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Strauss and some more modern composers, you have all violins sitting on the same side so that the sound image comes from the same place and arrives already mixed to the audience.

There is also a question in every concert about the double basses. Personally, I love big bass sounds and I want the audience to really hear them as the foundation of the music.

I love having bases along the back of an orchestra, as opposed to one side, so that the sound of the lowest note in the orchestra permeates through the orchestra and the whole sound (and intonation) of the orchestra is based on the bases (pun intended). Although of course, it depends on the acoustic properties of the venue and what sounds best.

However, there is some music for which the music written by the composer demands different orchestral textures and timbres. A great example is Stravinsky’s music for which you would place your bass section to one side so that the bass sonorities are clear and more separated from other instruments in the orchestra to best serve the way the music functions.

And then, of course, the complication is that you are not playing in venues that are all the same or with robots but real people. If you want the music in a certain way for the audience, you need to create conditions for the musicians to play to their best. The setting up of the orchestra also becomes a dialogue between your ideals, the venue and the players.

For the recording of the Symphony No. 1 from Franz Schmidt, I really wanted antiphonal violins, because I love that stereo sound and I felt there were a number of passages in the music where that would really add something. However, when we got into the sessions, the violins didn’t feel comfortable being so far away from each other (in the recording studio they struggled to hear each other from opposite ends of the stage). Because there are many passages with a lot of delicate details that they had to really get together as a singular violin section, the leader advised me to put them all on one side, which I did.

Suddenly they played with such confidence as they could all hear each other that it simply sounded so much better and outweighed my initial ideas. (This also shows the value of listening to what the players have to say – especially when they know their own orchestras and venues much better than you do!)

MF: Part of the design of stages is to control the loudness on stage, so the music is not too loud and you manage the noise exposure of the musicians. What are your views and experience on this?

JB: Well this is a very important issue, particularly at the moment. Modern orchestras accept (and even expect) the wearing of earplugs and sound protectors on stage as a normality. They are necessary to protect musicians who are seriously struggling with hearing loss after years of playing in orchestras – and even more in opera pits.

However, it is undeniable that the volume of orchestras has increased over the years. For a number of reasons – the halls we play in are often much bigger, the instruments have changed as well, all of which has developed symbiotically with a changing aesthetics of orchestral and instrumental sound.

In older halls like the Musikverein, you notice how loud a modern orchestra can sound. Whereas if you play in Chicago Symphony Centre, in The Shed in Tanglewood or the Royal Albert Hall, suddenly you have to develop this sound which projects and travels over huge distances.

For me, I have actually learned a lot from this phenomenon. The orchestras whose sound I love (Vienna Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic, Concertgebouw Orchestra or Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra) all play (or played) in smaller, old fashioned halls where making music isn’t about projecting your sound to the back of the 5000 seater hall, but more about creating warmth. Practically you don’t need to play too loudly in order for everyone just to hear, and so what you can do is discover more colours and nuances in the sound colours.

This idea has been central to my ideal of orchestral sound and, whilst both conducting and rehearsing, I often find myself asking orchestras to play softer, focusing on tone quality and warmth more than projection.

MF: What is your view on the quality of different styles of halls? Especially between shoebox and vineyard styles.

Yes, very interesting question. The first thing is that all musics are different. And I don’t just mean classical, pop, etc, I also mean Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Stravinsky, Boulez, etc. There is no absolute ‘perfect’ acoustic where you can play all music equally effectively. So even the idea that one style of hall is better acoustically and the other style better visually is not true (for me) because it depends on the repertoire being performed.

I have to say that I have experienced phenomenal concerts in both styles of hall and enjoyed performing in both, but I think the audience perspective is more important – at least it has to take into account the orchestra’s perspective because they are highly unlikely to perform a great concert if they are not comfortable on stage.

I love the social ideal in a vineyard hall (think Berlin Philharmonie, the New World Centre Miami, or the Leipzig Gewandhaus from the 1980s) that the audience is closer to the stage, they have better visual contact, and the hall doesn’t dissect communities by separating the expensive seats from the cheap seats.

However, I sat in many different seats in shoebox concert halls and felt incredibly connected to the stage – particularly when the halls aren’t too big (Concertgebouw, Musikverein, Snape Maltings or Berlin Konzerthaus).

Interesting to note that in the old style halls, the most expensive seats are normally at the front of the balcony which are the furthest from the stage, but of course still close enough to feel very connected.

I do think that we shouldn’t forget that music is an auditory art form. Whilst there are many ways to enjoy concerts, for social reasons, meditating on your day, enjoying the visual drama of the playing of the instruments, or just having a nice nap. But it is when somebody listens to the music actively that a live concert becomes something unique and nothing else in the world comes close. This is the experience we should all be striving for people to have.

MF: Can you share a little more about your favourite venues? There may be some you would advise people to go to or you have some interesting tips about some types of venues.

One of the cleverest halls is the Seiji Ozawa Hall in Tanglewood. It was completed in the 90s and in essence, it is a very traditional and fairly small shoebox with balconies. There is a summer festival there where the Boston Symphony Orchestra goes. The back wall of the hall can be folded out and opens to this sort of amphitheatre of a grass hill where people come, have picnic and listen to music all weekend. It is an amazing place.

It really has both the inside and the outside atmospheres. You get this wonderful, warm acoustic, and actually, over the six or seven years of conducting concerts there, the increase of moisture in the wood seems to have improved the warmth of the hall.

I think Suntory Hall in Tokyo is one of the most extraordinary halls. There is something magical about the sound there. The sound feels like you are not only close to the stage, but somehow you are also right at the back of the hall. Music sounds there as one single sound, it has this sort of visceral attack, very clean, very clear. You hear all the details and also the resonance of the space.

Opera houses also are very interesting. They are often quite dry. You have this small box in which the orchestra plays (the orchestra pit), and the sound goes vertically up from this pit, which the audience then hears mostly as reflected sound. You have singers on stage, who sing directly at the audience and the orchestra (allowing both to hear the singers clearly) and for the audience you get a wonderful balance between the reflected orchestral sound and the direct vocal sound. If you go to the Royal Opera House (London) or Palais Garnier (Paris) or even a smaller house like Gyndlebourne or the Comischer Oper (Berlin), the absolute best seats to hear a performance from are right at the very top at the very back (often the cheapest seats), but you will hear the most perfect sound. You hear this sort of shimmering effect, the balanced sound, the voice and the orchestra amplified in its own resonating chamber, as though the pit becomes part of the instrument of the orchestra like the body of a violin or the sound board on a piano. It’s an extraordinary experience.

Actually, almost the worst seats are at the first row of the stalls. At the first row, you are very close to the action visually, but the balance between the direct sound coming from the voice and the sound of the orchestra is unmixed and can sound separated. That’s also why when rehearsing for opera, you have somebody sitting in the front few rows balancing from there – normally if the balance is ok right at the front it will work everywhere else.

MF: For some halls, the acoustic conditions might not always be optimal depending on where you sit. The music you hear on stage could also be very different compared to the music you hear in the rest of the hall. How do you prepare for all this?

There are some concert halls where if you sit in the wrong seat, it might be an expensive seat, but if you sit in the wrong seat, it is really not a good experience. In a really good hall, there are very few differences between the seats.

What happens then is, most of the time, conductors or managers never sit in them. They judge performances from a very specific select set of locations. We forget sometimes that if you sit in a different place, you can hear something different.

An orchestra manager some years ago said to me “Look, you need to sit in every seat”. Because you need to know how every one of your audience feels. He was trying to find solutions to make all his audience happy. If we want to inspire people into music we love and make them hear what we want them to hear, we need to make sure we play well for every single seat.

Practically, to do this as a conductor, you often have somebody assisting you whose job is mostly to walk around the hall and give little notes back about how it sounds in the hall. I also find it hugely useful to have assistants, because they can conduct five minutes whilst you can walk around the hall and listen, so that you can really understand the translation from what it sounds like on the podium to what it sounds like in the hall.

There is another trick that I learned from one of my mentors, a conductor called Stanislav Skrowaczewski.

He used to occasionally turn 90 degrees to the orchestra, by putting his left ear towards the empty space, to listen to the hall.

You have to work at it a bit, but it gives you a really good sensation of what the hall sounds like, as opposed to when you are facing the orchestra where you hear mostly the direct sounds from the instruments.

Doing this gives you one more bit of information and it allows you can create a better balance between the sound of the orchestra and the reverberation of the hall, hopefully creating a fantastic sounding concert in every seat.